A vast network of underground fungi run the largest mining operation on the planet. Scraping specific minerals out of rocks, they deliver them to plants, who need these nutrients to grow. Fungi are invited to tunnel directly into the cells of plants, where they trade their mined minerals for the sugars that plants make.

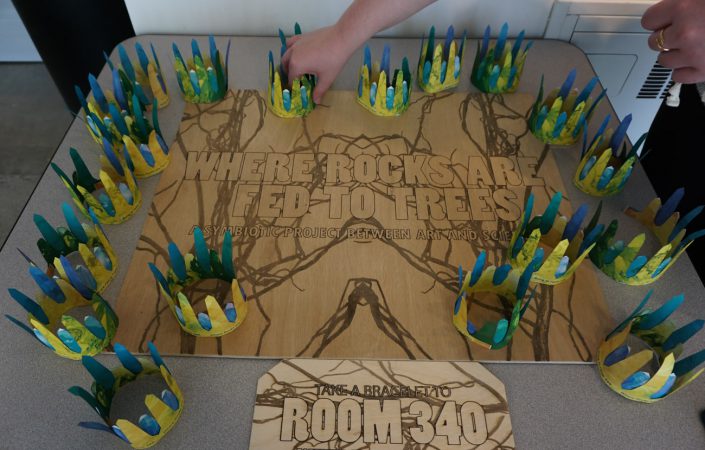

To experience scientific facts, which seem like fiction, the students and faculty of an art/science course created this installation, which models a fungal tunnel inside a plant cell and their symbiotic exchange of goods. The collaborative team sought to make science tangible, and to go beyond “visualization”.

An embodied, participatory experience was created that engaged all the senses. Modeling science was brought into a human scale and sensory understanding through movement, sound, vision, smell and taste. The smell of dirt was present, through bags of soil placed inside the tunnel and the addition of a synthetic dirt fragrance, geosmin. At the end of the tunnel there was a rock candy treat that participants exchanged for their mineral bracelet. It included a short text which explained: “You are a fungal body particle on its way into the depths of a plant’s private parts, its roots. Delivering your mineral, you are rewarded with sugar. Use it well, grow your network, and trade in peace”.

The experience allowed us – and visitors to the exhibition – to inhabit and “enact” the story of underground symbiosis.

Process

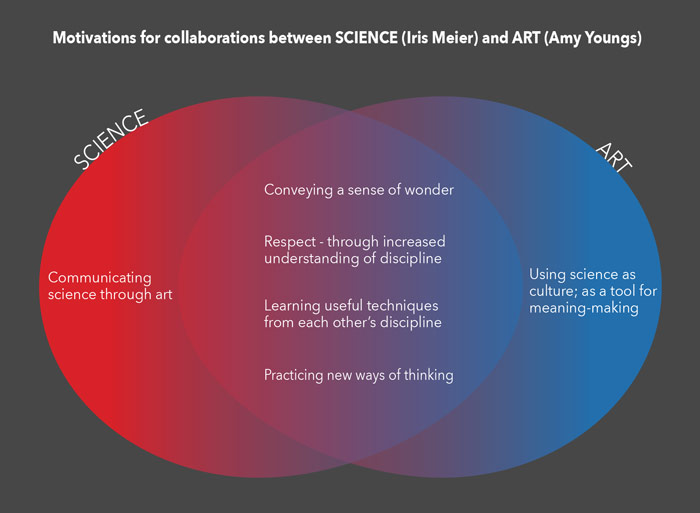

The collaboration between Dr. Iris Meier and Amy Youngs began three years previous to this project, when we first developed and taught a course called Harvesting Color: the Art and Science of Plant/Human Relationships. We have figured out symbiotic methods of teaching and working together and that acknowledges our distinct disciplines and our shared values. Often, for scientists, art is thought to be a good tool for visualizing or communicating science to the public. For artists, science is a powerful part of culture that we want to play with in our meaning-making projects.

The collaboration between Dr. Iris Meier and Amy Youngs began three years previous to this project, when we first developed and taught a course called Harvesting Color: the Art and Science of Plant/Human Relationships. We have figured out symbiotic methods of teaching and working together and that acknowledges our distinct disciplines and our shared values. Often, for scientists, art is thought to be a good tool for visualizing or communicating science to the public. For artists, science is a powerful part of culture that we want to play with in our meaning-making projects.

These motivations can sometimes be at odds during collaborations between our fields. We acknowledge that tension, and we work to focus on the areas where our motivations overlap. Generating work that can convey a sense of wonder is one of the reasons we collaborate.

Artists have important roles as cultural integrators of new scientific knowledge. Humans are not data-driven; we are story-driven.

We designed our most recent course, Underground Symbiosis: the art and science of mycorrhizal networks, to allow for an integrated approach to research, and co-creation within a classroom setting. We set out to co-author an artwork with each other that included all of the students in our class.

To begin, we used multiple modes to approach an understanding of the topic of symbiotic, mycorrhizal networks.

To begin, we used multiple modes to approach an understanding of the topic of symbiotic, mycorrhizal networks.

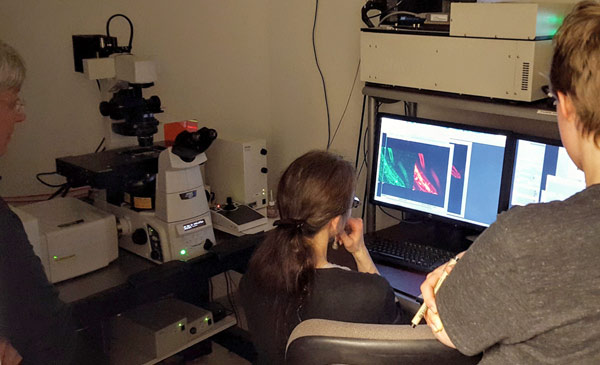

We practiced scientific methods, such as experiment design, and techniques such as microscopy, staining samples, and thin layer chromatography. We kept field notebooks to document our scientific experiments as well as our artistic experiments, drawings and ideas.

We grew soybeans plants, experimenting with adding symbiotic bacteria in some and nitrogen fertilizer in others. The images and ideas generated from the scientific experiments were often utilized in art assignments. Students produced short-term artworks in pairs; using artistic strategies such as amplification, transformation, combination, juxtaposition, distillation and metaphor.

Inspirations

We looked at artwork, reached out to experts, and visited several campus labs, such as the confocal microscope facility. All the while, we are asking each other, how do we convey this information to the public in an art installation?

We looked at artwork, reached out to experts, and visited several campus labs, such as the confocal microscope facility. All the while, we are asking each other, how do we convey this information to the public in an art installation?

We were inspired by a blog post in Scientific American “The World’s Largest Mining Operation is Run by Fungi”. This new knowledge really puts humans in our place, reminding us that we are not the most industrious. Scraping minerals out of rocks, fungi deliver them to plants. This story is ancient, as evidence of mycorrhizal fungi inhabiting plant cells comes from fossils more than 400 million years old. Fungi are invited to tunnel directly into the cells of plants, where they trade their mined minerals for the sugars that plants make. In order to live, fungi must find plant hosts. Plants have encouraged this symbiotic relationship for millennia; it may be vital for their continued survival.

Our installation, Where Rocks are Fed to Trees, models this interaction; casting human visitors as fungal particles, entering into the plant cell to re-enact a symbiotic relationship that has been occurring underground long before the appearance of humans on earth.

Our installation, Where Rocks are Fed to Trees, models this interaction; casting human visitors as fungal particles, entering into the plant cell to re-enact a symbiotic relationship that has been occurring underground long before the appearance of humans on earth.

Links to learn more about the fascinating symbiosis between plants and fungi:

- RadioLab episode, From Tree to Shining Tree

- BBC Plants Talk to Each Other Using an Internet of Fungus

- The New Yorker The Secrets of the Wood Wide Web

Scientific references:

Suzanne Simard (University of British Columbia), Giles Oldroyd (John Innes Centre), Maria Harrison (Boyce Thompson Institute), Uta Paszkowski (Cambridge).

Artist references:

Jorge Restrepo, Tomas Saraceno, Philip Beesley, Brandon Ballengee, Mei Ling-Hom, Ronald Van Der Meijs, Carsten Holler, Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey, Philip Ross, Gail Wight, Jae Rhim Lee, Mark Dion, Anil Podgornik.

Special thanks to our supporters:

The Department of Molecular Genetics, The Department of Art, College of Arts and Sciences Small Grant Program, Biological Sciences Greenhouse, and the Chadwick Arboretum

And thanks to the following individuals:

Eduardo Acosta, Dr. Ana Alonso, Jean-Christophe Cocuron, Dr. Anna Dobritsa, Anna Griffis, Norman Groves, Kim Landsbergen, Joan Leonard, Galen Rask, and Emily Yoders-Horn.